Why the “Kimwolf” Botnet Signals the Death of the Trusted LAN—and Why SASE is the Only Way Out.

We’ve spent the last five years arguing about perimeter security, debating the finer points of VPN concentrators and next-gen firewalls, while our employees went out and bought the Trojan Horse for $40 on Amazon.

It’s sitting in their living room right now. It’s plugged into the back of their 65-inch 4K TV. It’s on the same Wi-Fi network as your Corporate Controller’s laptop. And while your employee thinks it’s just a cheap way to watch the Premier League or pirated movies, it is actually a military-grade cyberweapon.

This isn’t hyperbole. The cybersecurity landscape of late 2025 has been defined by Kimwolf, a botnet that doesn’t attack from the outside—it lives inside. It has infested an estimated 1.8 million Android TV boxes, turning the “Work From Home” environment into a hostile operational theater.

If you are a CISO or a Network Architect, you need to stop looking at your perimeter firewall logs for a second and realize: the threat is already behind the wall. It’s watching Netflix, it’s mining crypto, and it’s selling your employee’s bandwidth to the highest bidder.

The “Living Room” Threat: A Reality Check

Let’s be honest: the “Return to Office” vs. “Remote Work” debate usually focuses on productivity or culture. But the real elephant in the room—the one we’re too polite to mention in board meetings—is that the average home network is a cesspool.

For years, we operated on a “Castle and Moat” philosophy. The office was the castle; the firewall was the moat. When COVID hit, we extended the moat via VPNs, pretending that if we could just encrypt the tunnel, the endpoint was safe.

Kimwolf proves that philosophy is dead.

Here is the reality of the threat landscape in 2026: The attacker isn’t a hoodie-wearing hacker trying to crack your password. The attacker is a supply chain defect. The attacker is the “gray market” electronics industry.

Kimwolf targets specific hardware: the unbranded or “off-brand” Android TV boxes (often listed as “SuperBOX,” “X96Q,” or “T95”) that flood marketplaces like Amazon and eBay. These aren’t Apple TVs or Rokus. These are cheap, powerful Android computers manufactured in Shenzhen with zero security oversight, often shipped with malware pre-installed at the factory.

When your employee connects one of these boxes to their Wi-Fi to watch “free” cable, they aren’t just getting piracy; they are volunteering their network to a global crime syndicate.

How the Trap Works: The “Free” VPN & The Monetization SDK

You might be asking, “How does a TV box compromise my corporate security?” It’s not magic; it’s capitalism.

The genius of Kimwolf—and its predecessor, the Aisuru group—is that they don’t always need to “hack” into a device in the traditional sense. They often just ask for permission, and users give it to them.

The Infection Vector

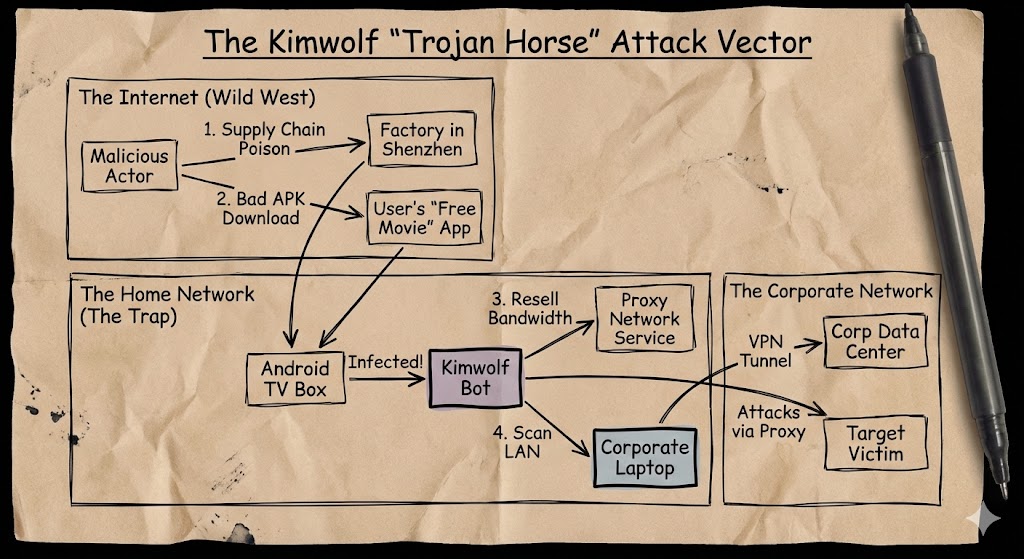

The infection usually happens in one of two ways, both of which are practically invisible to the user:

- Supply Chain Poisoning: In many cases, the firmware itself is poisoned. The box arrives with open (sometimes nonmalicious) backdoors, specifically an open Android Debug Bridge (ADB) port (TCP 5555) accessible to the wider internet. This is like buying a house where the back door doesn’t just lack a lock; it lacks a door.

- The “Trojanized” App Store: This is the more insidious method. Users download “Free VPN” apps, “Game Accelerators,” or “Free Streaming” APKs to bypass geo-blocks. Deep inside the code of these apps is a monetization SDK (Software Development Kit), often one called “ByteConnect”.

The Switch

Here is the trade: The user gets to watch their movie for free. In exchange, the SDK silently wakes up in the background and turns the device into a Residential Proxy Node.

To the user, the box just seems a little slow. To the rest of the internet, that box is now a “clean” exit node for cybercriminals. The operators of Kimwolf utilize this army of 1.8 million devices to sell access to other criminals—allowing them to route credit card fraud traffic, credential stuffing attacks, and ad-fraud bots through your employee’s IP address.

Researchers estimate the Kimwolf operators are generating nearly $88,000 per month just by reselling this bandwidth. It’s not just malware; it’s a business model.

The “Hotel Lobby” Metaphor

If you take nothing else away from this article, take this metaphor: Treat your employee’s home Wi-Fi like a public hotel lobby.

When you travel for business, you sit in a hotel lobby. You connect to the Wi-Fi. But you are paranoid. You know the guy in the trench coat sitting three tables away might be sniffing packets. You know the hotel router hasn’t been patched since 2018. So, you trust nothing. You rely entirely on the security on your device and the encrypted tunnel it creates.

Why do we treat the home office differently?

Right now, your Senior Developer is sitting at home. On their left is their corporate MacBook, holding the keys to your source code. On their right, plugged into the same mesh router, is a compromised $40 Android box that is currently participating in a 30 Terabit-per-second (Tbps) DDoS attack against a gaming company.

That box is inside the firewall. It has local LAN access. It can scan for printers. It can ping the MacBook. If your developer has “File Sharing” enabled or a weak local firewall, that “TV box” can pivot.

We have to stop trusting the LAN. The LAN is dirty. The LAN is compromised.

Why Legacy Security Can’t See It

“But Ed,” you might say, “I have endpoint protection! I have firewalls!”

Here is the bad news: Your legacy gear is blind to this. Kimwolf is engineered to look like normal traffic. It uses two specific technologies to stay invisible, and frankly, they are brilliant:

- DNS-over-TLS (DoT): Old-school botnets were loud. They would reach out to

evil-hacker-site.comon port 53, and your firewall would block it. Kimwolf uses DNS-over-TLS on port 853. To your firewall, this traffic looks like an encrypted, legitimate conversation with a Google or Cloudflare DNS server. The malicious request is hidden inside the TLS tunnel. You can’t block what you can’t read. - EtherHiding & Blockchain Domains: This is the “checkmate” move. When security researchers try to take down a botnet, they usually seize the domain name. Kimwolf operators anticipated this. They use Ethereum Name Service (ENS) domains, like

pawsatyou.eth. These aren’t standard web domains; they are smart contracts on the Ethereum blockchain. You cannot send a court order to the blockchain. You cannot “seize” a crypto wallet. The Command-and-Control (C2) IP address is stored on the blockchain, and the malware just looks it up. It makes the infrastructure virtually uncensorable.

The Solution: SASE is the Bubble

So, the sky is falling. The call is coming from inside the house. What do we actually do?

We stop trying to clean the ocean. You are never going to patch every cheap IoT device in your employees’ homes. You cannot police what they buy on Amazon, and returning everyone to the office doesn’t fix it, unless you prohibit all remote work and chain laptops to desks.

Instead, we have to invert the model. We need SASE (Secure Access Service Edge).

SASE is often sold as a “cloud transformation” buzzword, but in this context, it is a survival mechanism. SASE allows us to wrap a cryptographic bubble around the corporate asset, regardless of where it physically sits.

1. Zero Trust Network Access (ZTNA)

We need to kill the VPN. A VPN connects a device to a network. That’s bad. If the device is compromised (or if a lateral mover jumps from the TV box to the laptop), the VPN becomes a highway to your data center. ZTNA connects a user to an app. It doesn’t matter if the laptop is on a dirty home network. The ZTNA agent creates a micro-tunnel directly to the application (Salesforce, AWS, Jira). It ignores the local LAN completely. The “TV Box” can scan all day; it will never see the traffic inside that tunnel.

2. Endpoint Isolation

Your corporate policy needs to enforce “Host Isolation” on remote endpoints. The corporate laptop should essentially act as if it is alone in the universe. Inbound connections from the local LAN should be dropped by default. No printer sharing. No iTunes syncing. Total isolation.

3. Inspecting the “Normal”

Since Kimwolf uses residential proxies to hide, “normal” is no longer a whitelist criteria. We need SASE platforms that perform SSL/TLS inspection at scale. We need to be able to crack open those “encrypted DNS” packets and see that they are actually calling out to a known botnet command center, even if they are dressed up as Google traffic.

The Human Element: Don’t Blame the User

Finally, a note on culture. It is tempting to blame the user. “Why did you buy that cheap piece of junk?” “Why did you download that shady VPN?”

Don’t do that. It’s a losing battle.

Human nature is to seek the best deal. If a box promises “Free NFL Sunday Ticket” for a one-time payment of $50, people will buy it. If an app promises faster gaming speeds, kids will install it.

Our job as security leaders isn’t to change human nature. It’s to build an architecture that survives it.

We have to assume the home network is hostile. We have to assume the “Smart Toaster” is listening and the “Android TV” is attacking. We have to build our networks so that when—not if—those devices get infected, it simply doesn’t matter.

The Kimwolf botnet is a wake-up call. The “trusted network” is a relic of the past. The only thing you can trust is the cryptographic bubble you build around your data.

So, let the TV box mine its crypto. Let it run its proxy scams. Just make sure your corporate data is watching from a safe, encrypted distance.